Ernesto Che Guevara, “santificato” in morte, ma non in vita. Antologia di testi

- Tag usati: che_guevara, comunismo

- Segnala questo articolo:

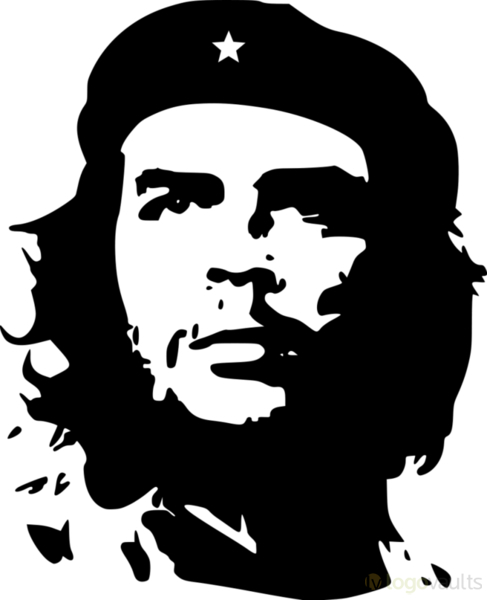

Riprendiamo sul nostro sito alcuni testi parziali, ma veri nella sostanza. Li pubblichiamo, sapendo bene che una visione completa della vita e dell’opera di Che Guevara richiederebbe ben altro spazio, solamente al fine di fornire elementi per un giudizio più equilibrato e non agiografico del Che – è a tutti noto che “Che” significa semplicemente proveniente dall’Argentina; si potrebbe dire, ad esempio, “el Che Maradona”, cioè “Maradona che viene dall’Argentina”. Che Guevara fu, al pari di molti altri della sua epoca, al contempo un uomo che lottava contro le ingiustizie ed un uomo che generava ingiustizie, un uomo che lottava per la pace ed un uomo che uccideva ingiustamente, perché troppo forte era il suo debito verso il marxismo e la visione della storia e dell’uomo propugnata da quell’ideologia. L’immagine di Che Guevara è diventata “icona” - oggi paradossalmente “icona” commerciale - solo a motivo della sua morte violenta: fu la sua sofferenza in morte, e non le violenze commesse in vita, a permetterne la sua “santificazione” laica. Per approfondimenti, cfr. la sotto-sezione Il novecento: il comunismo nella sezione Storia e filosofia.

Il Centro culturale Gli scritti (19/10/2014)

1/ Fidel Castro chiede scusa ai gay «Perseguitati, la colpa è mia»

Riprendiamo da L’Unità del 31/8/2010 un breve articolo redazionale. Restiamo a disposizione per l’immediata rimozione se la presenza sul nostro sito non fosse gradita a qualcuno degli aventi diritto. I neretti sono nostri ed hanno l’unico scopo di facilitare la lettura on-line.

Il Centro culturale Gli scritti (19/10/2014)

Fidel Castro chiede scusa agli omosessuali per averli perseguitati a Cuba negli anni '60 e '70. «Se qualcuno è responsabile, sono io. Non darò la colpa a nessuno», ha dichiarato Castro, 84 anni, in un'intervista al quotidiano messicano La Jornada, rilanciata dai media cubani. «Personalmente non ho pregiudizi», ha dichiarato l'ex presidente secondo cui l'aver inviato i gay in campi di lavoro agricolo-militari, sia stata «una grande ingiustizia».

In una sorta di contrappasso la nipote, Mariela Castro, psicologa di 47 anni, figlia del presidente Raul, capeggia la lotta contro la discriminazione dei gay. L'omosessualità è stata depenalizzata a Cuba solo nel 1997.

2/ Le accuse di crimini durante il regime (dalla voce Che guevara in Wikipedia al 6/10/2014)

Riprendiamo una sezione dalla voce Che guevara in Wikipedia alla data del 6/10/2014. Restiamo a disposizione per l’immediata rimozione se la presenza sul nostro sito non fosse gradita a qualcuno degli aventi diritto. I neretti sono nostri ed hanno l’unico scopo di facilitare la lettura on-line. Ovviamente non è stato possibile verificare, se non parzialmente, le fonti citate da Wikipedia.

Il Centro culturale Gli scritti (19/10/2014)

Alcuni autori hanno accusato Guevara di aver commesso crimini contro l'umanità e violazioni dei diritti umani, usando l'autorità che gli era stata conferita nell'ambito dell'esercito rivoluzionario. Di questi riferiscono in particolare Il libro nero del Comunismo[1] e lo scrittore Alvaro Vargas Llosa, anche sulla base di quanto scritto dal Che nel proprio diario[2], ma anche altri autori[3].

Alcuni di questi hanno affermato come gli episodi di violenza che imputano a Guevara siano conseguenza anche della sua concezione ideologica, che reputano esemplificata tra l'altro dalla seguente dichiarazione del Che, da essi non raramente citata:

«L'odio come fattore di lotta; l'odio intransigente contro il nemico, che permette all'uomo di superare i suoi limiti naturali e lo trasforma in una efficace, violenta, selettiva e fredda macchina per uccidere. I nostri soldati devono essere così: un popolo senza odio non può distruggere un nemico brutale. Bisogna portare la guerra fin dove il nemico la porta: nelle sue case, nei suoi luoghi di divertimento. Renderla totale. Non bisogna lasciargli un minuto di tranquillità [...] farlo sentire come una belva braccata» (dal Messaggio alla Tricontinental[4], articolo di Ernesto Guevara pubblicato[5] sulla rivista Tricontinental all'Avana il 16 aprile 1967[6], leggibile in italiano[7]).

Accuse di crimini vengono mosse anche in relazione al ruolo che Che Guevara ha avuto come giudice d'appello nel contesto dell'applicazione delle cosiddette "Ley de la Sierra": si trattava di una normativa penale risalente al XIX secolo[8]. Tali "Ley de la Sierra" comminavano la pena capitale per numerosi crimini[9] e vennero estese all'intero territorio cubano nel 1959, allo scopo di perseguire coloro che erano considerati "criminali di guerra" ed oppositori politici.

Nel corso dei processi tenutisi a La Cabana nel periodo summenzionato venne inflitta la pena di morte per fucilazione[10] a molte persone, seppure le fonti siano discordi sul numero esatto dei fucilati[11]. A La Cabana furono istituiti due tribunali rivoluzionari, uno per giudicare poliziotti e soldati, uno per i civili[12]; Guevara non era membro di nessuno dei due, ma, nella sua posizione di comandante della guarnigione, esaminava le richieste di appello ed i direttori dei tribunali erano suoi subordinati[13].

Tali processi e le relative esecuzioni sono state tacciate di arbitrarietà: il rispetto dei diritti dell'imputato, come la presunzione d'innocenza ed il diritto ad un giusto processo, secondo i critici, sarebbe stato meramente formale e non sostanziale, il che sarebbe dimostrato dalla brevità dei procedimenti giudiziali e dalla violazione fattuale del diritto di difesa[14]. Si sarebbe trattato in sostanza di processi farsa, nei quali non sarebbero stati coinvolti solo criminali di guerra ma soprattutto semplici oppositori politici[15]. Il modo in cui i processi vennero condotti e le condanne inflitte suscitarono scandalo e proteste presso la stampa occidentale ed in particolare presso il Time[16].

Alvaro Vargas Llosa afferma che, in base alle testimonianze raccolte nelle sue ricerche, coloro che furono fucilati all'Avana nel periodo di comando di Guevara potrebbero superare il numero di 2000 persone[17] e sostiene che già nel 1959 Guevara si sarebbe reso responsabile dell'esecuzione sommaria di numerosi oppositori politici[18].

Nel 1960 inaugura il sistema concentrazionario cubano, venendo posto a capo del primo campo di concentramento castrista, creato quell'anno a Guanahacabibes sulla penisola di Guahana allo scopo di punire, per stessa ammissione di Guevara, "la gente che ha mancato nei confronti della morale rivoluzionaria"[19]. Il periodo di attività del campo si protrasse ben oltre il periodo in cui Guevara ne fu a capo[20]. In particolare, nel 1965 Guevara introdusse a Cuba il sistema delle Unità Militari di Aiuto alla Produzione (UMAP), dove vennero detenuti e sottoposti a tortura intellettuali contrari alla dittatura Castrista, dissidenti politici, omosessuali e religiosi (tra cui cattolici, testimoni di Geova, evangelisti e avventisti)[21]. Tali accuse gli sono state imputate anche dai saggisti Jay Nordlinger e Massimo Caprara, ex segretario personale di Palmiro Togliatti [22].

Régis Debray, ideologo dei focolai di guerriglia rivoluzionari e compagno di Guevara in Bolivia, affermò con riferimento a questi che «è stato lui e non Fidel a ideare il primo "Campo di lavoro correzionale"»[23]. Guevara è stato visto da alcuni come la mente del regime castrista nella sua prima fase di vita (all'incirca tra il 1959 ed il 1965) ed è stato pertanto considerato responsabile o comunque complice dei crimini commessi in questa parte della storia di Cuba[24], ma anche della politica di collettivizzazione delle campagne[25].

Riguardo alla persecuzione degli omosessuali Castro ha però, nel 2010, chiesto pubblicamente scusa, affermando di esserne lui e non Guevara l'artefice, sostenendo difatti che «se qualcuno è responsabile, sono io. Non darò la colpa a nessuno».[26]

3/ Che Guevara sconosciuto, di Massimo Caprara

Riprendiamo dalla rivista "Il Timone" n. 20, Luglio/Agosto 2002, un articolo di Massimo Caprara, ex-segretario personale di Palmiro Togliatti. Restiamo a disposizione per l’immediata rimozione se la presenza sul nostro sito non fosse gradita a qualcuno degli aventi diritto. I neretti sono nostri ed hanno l’unico scopo di facilitare la lettura on-line.

Il Centro culturale Gli scritti (19/10/2014)

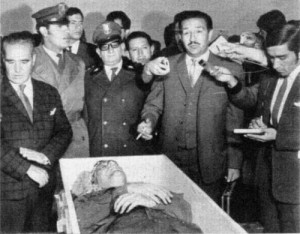

Verso l'una e dieci del pomeriggio di domenica 9 ottobre 1967, il guerrigliero catturato - ha un berretto nero, un'uniforme militare assai sporca, una giacca azzurra con cappuccio, il petto quasi nudo, la camicia senza bottoni - sistemato provvisoriamente su una panca, con i polsi legati, è ucciso, mentre ancora gli sanguina una ferita alla gamba destra. E' finito da una scarica a bruciapelo di un mitra M-2. Le ultime parole che ha proferito nei confronti del sottufficiale dei rangers governativi boliviani Mario Teràn sono state di sonante disprezzo: "Spara, vigliacco, che stai per uccidere un uomo".

Il guerrigliero cadde a terra con le gambe maciullate, contorcendosi e perdendo copiosissimo sangue. Altri due sottufficiali, entrati ubriachi nella stanza, spararono ciascuno un colpo, direttamente sul volto. Poco lontano, dal villaggio di La Higuera, dove sono giunti agenti della CIA, nei pressi della gola Quebrada del Yuro, un sacerdote domenicano d'una parrocchia vicina, padre Roger Schiller, arrivò trafelato a cavallo. "Voglio confessarlo, so che ha detto: sono fritto. Voglio dirgli: lei non è fritto, Dio continua a credere in lei".

Nel pomeriggio, il comandante del reparto boliviano, che è il maggiore Ayoros, dispone che il corpo venga adagiato su una barella e gli venga legata la mandibola con un fazzoletto perchè il volto non si scomponga. Un fotografo ambulante ritrasse i soldati e il sacerdote intento a lavare le macchie di sangue. L'elicottero volò allora in alto con il corpo sfigurato del guerrigliero. Al sottufficiale Teràn hanno promesso un orologio e un viaggio a West Point per frequentare un corso. Egli ha ucciso il comandante Ernesto Guevara Lynch, detto il Che, medico argentino che, con decreto governativo del 9 febbraio 1959, è stato naturalizzato cubano per servizi resi alla Rivoluzione. Da allora prese corpo la sentita e appassionante leggenda di un autentico santo laico.

"Dalle migliaia di foto, posters, magliette, dischi, video, cartoline, ritratti, riviste, libri, frasi, testimonianze, fantasmi di questa società industriale, il Che ci guarda attento. La sua immagine attraversa le generazioni, il suo mito passa di corsa in mezzo ai deliri di grandezza del neoliberismo. Irriverente, beffardo, moralmente ostinato, indimenticabile", scrive in un libro, edito in italiano nel 1977 con il titolo "Senza perdere la tenerezza", Paco Ignazio Taibo II. Lo scrittore, nato a Gijon in Spagna, coglie drammaticamente il vero.

La figura assieme virile e dolce del Che Guevara, il cui motto è appunto: "Bisogna essere duri senza mai perdere la tenerezza", attraversa come un lampo la storia del secolo da poco passato; dalla nascita in una famiglia della buona borghesia alla giovinezza nomade e ribelle, dall'epica avventura sulla Sierra Maestra con l'amico Fidel Castro, alle responsabilità nelle istituzioni di "Cuba libera ma assediata dall'embargo statunitense", fino al tragico eccidio sui monti della Bolivia ed alla immediata nascita di un mito eroico, unico nei nostri tempi. Lui è sempre al fianco di Fidel, sempre con un itinerario ideale diverso, cioè più organicamente comunista, come è stato osservato, nel 1967, dallo scrittore Carlos Franqui che abbandonerà Castro. "Doveva essere accecante se anche i più opachi, al suo passaggio, erano illuminati".

Regis Debray, l'intellettuale francese oggi vivente che lo raggiunse in Bolivia, ha scritto molto su di lui e sulla sua condotta nel libro "Révolution dans la révolutrion" e in "Loués soient nos seigneurs", edito a Parigi da Gallimard nel 1996. Egli ha tracciato un disincantato e veritiero affresco sulle incarnazioni del catrismo, come "lunga marcia dell'America Latina" e sulle sue diverse varianti. Che Guevara materializza quella più irriducibile, severa, spietata e crudele: a mezza strada tra la violenza pro-bolscevica della CEKA e della GPU e la ferocia primordiale perpetrata nelle campagne cinesi dal maoismo. Per Debray, egli è "il più austero tra i praticanti del socialismo". E' un medico, afflitto fin dal 1930 (era nato il 14 luglio del 1928 nella città di Rosario) da un inguaribile asma che lo farà soffrire nelle sue trasferte guerrigliere in Africa e in America Latina. Forse anche per questo è in grado di meglio conoscere le tecniche più dolorose della punizione e segregazione per i dissidenti detenuti.

Un'inflessibile ideologia con il corredo di una raffinata metodologia di persecuzione fisica.

Il Che, sin dalla clandestinità, polemizza duramente con i combattenti del "Llano", la pianura, contrapponendo alla loro malleabilità la durezza di condotta osservata in montagna, nella Sierra. Attacca Castro per lo scarso rigore e lo definisce per un pezzo, sprezzamente, come "il leader radicale della borghesia di sinistra", sensibile alle sirene del policantismo. Egli è in linea pregiudiziale sempre "favorevole ai processi sommari" e di lui si ricorda l'ingiunzione perentoria ai ribelli venezuelani: "Prendete un fucile e sparate alla testa di ogni imperialista che abbia più di quindici anni". Al punto che Debray, riassumendo, lo caratterizza come un "dogmatico, freddo, intollerante che non ha nulla da spartire con la natura calorosa e aperta dei cubani". Intelligente e risoluto, generoso ed egualitario con i suoi, come inflessibile con i nemici, comanda energicamente il secondo Fronte di Las Villas nella conquista dell'esercito ribelle a Cuba.

Durante l'avanzata, nel 1957, si distingue per l'efferatezza con la quale interpreta il suo modo di essere rivoluzionario e di liquidare nemici e presunti traditori. Eutimio Guerra, un guerrigliero, viene accusato di avere avuto una colusione con il nemico, cioè con l'esercito del dittatore Fulgencio Batista, e immediatamente deferito ad un'improvvisata Corte marziale.Il Che anticipa il verdetto. Raccontò successivamente un suo commilitone detto "Universo": "Io avevo un fucile e in quel momento il Che tira fuori una pistola calibro 22 e pac, gli pianta una pallotola qui. Che ha fatto? Lo hai ucciso. Eutimio cadde a pancia in su, boccheggiando".

Nell'anno della "liberazione" di Cuba, che è il 1959, il Che viene convocato da Castro e il 7 settembre riceve l'incarico provvisorio di Procuratore militare. E' una convulsa ma intensa fase della nuova Cuba che ne prefigura i caratteri sociali e civili, che deve giudicare i collaborazionisti con il passato regime, processarli e soprattutto toglierli dalla circolazione. L'anno dopo, ai primi di gennaio, si apre a Cuba il primo "Campo di lavoro correzionale" (ossia di lavoro forzato). E' il Che che lo dispone preventivamente e lo organizza nella penisola di Guanaha. Trecentoottantuno prigionieri, arresisi alle truppe castriste sull'Escambray, vengono radunati, incarcerati a Loma de lo Coches e tutti fucilati.

Jesus Carrera, anticastrista che è stato ferito negli scontri, chiede la grazia. Il Che gliela rifiuta ritenendolo un antagonista personale del capo Fidel. La stessa sanguinosa procedura viene riservata a Humberto Sori Marìn per il quale aveva chiesto misericordia la madre. Sotto l'impegnativa e organica inclinazione del Che, prende corpo la "DSE", il Dipartimento della Sicurezza di Stato, anche con il nome di "Direcciòn general de contra-intelligencia". Un dettagliato regolamento elaborato puntigliosamente dal medico argentino, fissa le punizioni corporali per i dissidenti recidivi e "pericolosi" incarcerati: salire le scale delle varie prigioni con scarpe zavorrate di piombo; tagliare l'erba con i denti; essere impiegati nudi nelle "quadrillas" di lavori agricoli; venire immersi nei pozzi neri.

Marta Frayde, già rappresentante di Cuba all'Unesco e, dopo i primi anni, incarcerata, ha descritto le celle riservate ai "corrigendi": sei metri per cinque, ventidue brandine sovrapposte, in tutto quarantadue persone in una cella. Le accuse nei Tribunali sommari rivolte ai controrivoluzionari vengono accuratamente selezionate e applicate con severità: religiosi, fra i quali l'Arcivescivo dell'Avana, Monsignor Jaine Ortega; adolescenti e bambini; omosessuali. La fortezza La Cabana di Santiago viene utilizzata come centro di smistamento. Il procuratore Guevara Lynch illustra a Fidel Castro e applica un "Piano generale del carcere", definendone anche la specializzazione, Vengono così organizzate le case di detenzione "Kilo 5,5" a Pinar del Rio. Esse contengono celle disciplinari definite "tostadoras", ossia tostapane, per il calore che emanavano. La prigione "kilo 7" viene frettolosamente fatta sorgere a Camaguey: una rissa nata dalle condizioni atroci procurerà la morte di quaranta prigionieri. Il campo di concentramento La Cabanas ospita le "ratoneras", “buchi di topi”, per la loro angustia. La prigione Boniato comprende celle con le grate chiamate "tapiades", nelle quali il poeta Jorge Valls trascorrerà migliaia di giorni di prigione. Il carcere "Tres Racios de Oriente" include celle larghe un metro, alte un metro e ottanta centimetri e lunghe dieci metri, chiamate "gavetas". La prigione di Santiago "Nueva Vida" ospita cinquecento adolescenti. Quella "Palos", bambini di dieci anni, quella "Nueva Carceral de la Habana del Est", omosessuali dichiarati o sospettati. Ne parla il film su Reinaldo Arenas "Prima che sia notte", di Julian Schnabel uscito nel 2000.

Il Che lavora con strategia rivolta non solo al presente ma al futuro Stato ditattoriale. Nel corso dei due anni passati come responsabile della Seguridad del Estado, avendo come collaboratore Osvaldo Sanchez che era esperto principale comunista, si materializza la persecuzione contro la Chiesa. Pascal Fontaine, nel suo libro "America Latina alla prova", calcola che centotrentuno sacerdoti hanno perduto la vita fino al 1961 nel periodo in cui Guevara era artefice massimo del sistema segregazionista dell'isola. Viene definito "il macellaio del carcere-mattatoio di La Cabana". Si oppone con forza alla proposta di sospendere le fucilazioni dei "criminali di guerra". Più che da Danton discende dall'incorruttibile, l'"incorruptible" Robespierre. Quando ai primi del 1960 a lui viene assegnata la carica di Presidente del banco Nacional, Fidel lo ringrazia con calore per la sua opera repressiva.

Egli ne generalizza ancor più i metodi per cui ai propri nuovi collaboratori, per ogni minima mancanza, minaccia "una vacanza nel campo di lavoro di Guanahacabibes". Il medico argentino, il più coerente leninista dell'America Latina, il meno reticente delle proprie idee e propositi pratici, è l'autentico motore di una ideologia totalitaria e di una macchina penitenziaria statale. La sua azione, esplicitamente ispirata ad una concezione coercitiva, impersona, come egli scrisse: "l'odio distruttivo che fa dell'uomo un'efficace, violenta, selettiva, fredda macchina per uccidere".

4/ Non si difende Cuba il giorno del Gay Pride

Riprendiamo dal sito dell’Associazione un Comunicato dell’Arcigay emesso il 21/6/2003. Restiamo a disposizione per l’immediata rimozione se la presenza sul nostro sito non fosse gradita a qualcuno degli aventi diritto. I neretti sono nostri ed hanno l’unico scopo di facilitare la lettura on-line.

Il Centro culturale Gli scritti (19/10/2014)

Il 28 giugno 1969, a New York, la comunità gay, lesbica e trans della città si ribellò alle violenze della polizia locale che aveva aggredito per l’ennesima volta gli avventori del bar Stonewall, dando vita alla prima manifestazione omosessuale contro l’intolleranza e la discriminazione sociale. Da quel giorno, ogni anno, in tutto il mondo si celebra il Gay Pride, la giornata dell’orgoglio gay, lesbico e transgender, la fine dell’invisibilità e l’affermazione della loro identità in modo aperto.

Il prossimo 28 giugno a Roma avrà luogo un evento di segno molto diverso. Il comitato “Difendiamo Cuba” ha lanciato una manifestazione di solidarietà al regime di Fidel Castro a cui hanno aderito importanti forze della sinistra italiana, dal PdCI a Rifondazione, da “Socialismo 2000” ad alcuni parlamentari Verdi. In questi stessi giorni, Amnesty International continua a denunciare inascoltata sia la crescente violazione dei diritti umani a Cuba, sia le responsabilità dell’embargo commerciale che, strangolando l’economia cubana, viene utilizzato come giustificazione per la repressione dei diritti ed i cui effetti negativi sulla nutrizione, la salute, l'educazione non agevolano un percorso di democratizzazione di Cuba.

Fra i diritti violati a Cuba ci sono quelli delle persone omosessuali e transessuali, ancora privi della possibilità di camminare a testa alta in un ambiente sicuro, impediti nei loro diritti fondamentali e sottoposti al ricatto della legge. E’ per questo che non ci ha fatto per niente piacere sapere che gran parte della sinistra italiana si ritroverà proprio in quella data a noi così cara a difendere le politiche di un regime che impedisce a gay, lesbiche e trans di essere se stessi alla luce del sole.

A Cuba la combinazione fra il tradizionale machismo culturale delle aree latine e la subordinazione ideologica dei diritti individuali a quelli sociali tipica dei paesi del socialismo reale hanno creato una combinazione particolarmente esplosiva per i gay.

Negli anni sessanta gli omosessuali venivano spediti ai lavori forzati. Nel 1971 il primo Congresso sull'educazione e la cultura sancì che "le manifestazioni di omosessualità non possono essere tollerate", con la conseguenza dell'espulsione da scuole e università di studenti e docenti gay. Nel 1978 ai medici omosessuali venne impedito l'esercizio della professione e lo Statuto dei lavoratori stabilì il licenziamento dei lavoratori gay.

Nel 1980 il regime decise di allentare un po’ la pressione offrendo alle persone omosessuali, come ad altri soggetti considerati antisociali, la possibilità di lasciare Cuba. L’atteggiamento del governo cubano oscillò per alcuni anni fra repressione normativa e una certa tolleranza effettiva.

Il codice penale del 30 aprile 1988 confermò che rendere pubblica la propria omosessualità, così come fare "avances amorose omosessuali", fosse punito da tre mesi ad un anno. Sfidando l’arresto, il 28 luglio del 1994 un gruppo di gay e lesbiche, riuniti al Parco Almendares all’Avana, diede vita alla prima Associazione Cubana Gay e Lesbica. Nel settembre 1995, alla IV Conferenza delle Donne di Pechino, Cuba aderì alla proposta di inserire un riferimento all’orientamento sessuale nel documento programmatico, lasciando intravedere la possibilità di una nuova fase. Ma non durò a lungo.

Nel 1997 il governo mise in atto un giro di vite. L’Associazione formata nel 1994 fu sciolta e i suoi membri messi agli arresti domiciliari per qualche tempo. Da allora non è più stato possibile realizzare l’obiettivo della costruzione di una socialità gay alla luce del sole. La repressione della polizia verso i luoghi d’incontro gay, informalmente sorti all’Avana, non si è allentata. L’accesso delle coppie dello stesso sesso ai locali pubblici è stato limitato dalla polizia. Le retate nei locali si sono intensificate: ne hanno fatte le spese anche il regista Pedro Almodovar e lo stilista francese Jean Paul Gaultier, arrestati nel settembre 1997 insieme a centinaia di altri clienti della più popolare discoteca frequentata da gay dell’Avana, El Periquiton, e rilasciati il giorno dopo dietro il pagamento di una multa.

Qualche settimana fa, un importante esponente dell’ambasciata cubana in Italia ha confermato pubblicamente, rivendicandone la giustezza, la norma per cui gli insegnanti gay sono espulsi dalle scuole cubane: un gay in cattedra determinerebbe l’orientamento sessuale dei bambini. Meglio il licenziamento, e per giusta causa.

L’idea che per difendere le conquiste sociali o l’indipendenza di Cuba si debbano negare diritti civili fondamentali non ci convince né ci piace. La libertà non è un mezzo, e la sua violazione non può essere giustificata chiamando in causa principi sovraordinati a cui sacrificare l’esistenza concreta di donne e uomini. Né ci sembra accettabile l’idea che negare diritti a gay, lesbiche e trans sia necessario per tutelare valori più alti. Combattiamo tenacemente questa impostazione, si tratti dell’Iran di Khatami, dell’Italia di Woityla o della Cuba di Castro.

Per questo chiediamo agli organizzatori della manifestazione in difesa di Cuba di accogliere questa nostra richiesta: spostate la data della manifestazione. Liberate il 28 giugno da una sovrapposizione lacerante. Date al governo di Castro un segnale chiaro, che segni la distanza dell’opinione pubblica italiana, anche di quella più vicina a Cuba, da un’inutile e dolorosa repressione dell’identità di migliaia di donne e uomini che reclamano solo di essere liberamente se stessi.

Sergio Lo Giudice; Franco Grillini; Aurelio Mancuso; Alberto Baliello; Michele Bellomo; Andrea Benedino; Giovanni Dall'Orto; Alessio De Giorgi; Edoardo Del Vecchio;Marcella Di Folco; Paolo Ferigo; Riccardo Gottardi; Cristina Gramolino; Mirella Izzo; Massimo Mazzotta; Fabio Omero; Vanni Piccolo; Luca Ruiu; Renato Sabbadini; Gianpaolo Silvestri; Delia Vaccarello; Luigi Valeri; Gianni Vattimo; Alessandro Zan;

Nota de Gli scritti: Per approfondimenti sul tema cfr. Félix Luis Viera, Il lavoro vi farà uomini. Omosessuali e dissidenti nei gulag di Fidel Castro, Edizioni Cargo, 2005.

5/ Il Messaggio del Che alla Tricontinental

Riprendiamo dal web il passaggio del Messaggio di Che Guevara pubblicato sulla rivista Tricontinental (Messaggio alla Tricontinental, articolo di Ernesto Guevara pubblicato sulla rivista Tricontinental all'Avana il 16 aprile 1967) che incita all’odio: sebbene il testo debba essere inserito nel cotesto del Messaggio che è una lettura della situazione politico-economica del tempo alla luce della lotta di classe, le sue parole pesano come macigni ed hanno formato le menti dei giovani di quella generazione.

Il Centro culturale Gli scritti (19/10/2014)

Il grande insegnamento della invincibilità della Guerriglia farà presa sulle masse dei diseredati. La galvanizzazione dello spirito nazionale, la preparazione a compiti più duri, per opporsi a repressioni più violente. L'odio come fattore di lotta - l'odio intransigente contro il nemico - che spinge oltre i limiti naturali dell'essere umano e lo trasforma in una reale, violenta, selettiva e fredda macchina per uccidere. I nostri soldati devono essere così, Un popolo senza odio non può vincere un nemico brutale.

6/ La ragazza che vendicò Che Guevara. Storia di Monika Ertl

J. Schreiber (La ragazza che vendicò Che Guevara. Storia di Monika Ertl, Nutrimenti, Roma, 2011), racconta la vicenda di Monika Ertl, figlia di Hans Ertl (1908-2000), cameraman nazista che emigrò dopo la guerra in Bolivia.

In Bolivia, precisamente il 9 ottobre 1967 a La Higuera, venne ucciso Che Guevara. Il suo cadavere venne trasferito poi a Vallegrande dove il maggiore Roberto Quintananilla, dinanzi al macabro ed osceno dilemma se decapitarlo o tagliargli le mani, per provarne nei gionri successivi la morte, scelse la seconda soluzione.

Il 9 settembre Quintanilla, avanzato in carriera anche grazie alla spedizione contro il Che, guidò il gruppo di polziotti che uccise un altro rivoluzionario, Inti Peredo, a La Paz il 9 settembre 1969. In quell’occasione Quintanilla, che era stato fin lì restio ad esporsi in pubblico, si fece fotografare con il cadavere di Inti Peredo.

Monika Ertl, divenuta nel frattempo rivoluzionaria, dinanzi a quella foto decise che avrebbe vendicato il Che uccidendo Quintanilla. Vi riuscì il 1 aprile 1971 nel consolato boliviano di Amburgo in Germania, dove il Quintanilla era stato inviato per sfuggire al pericolo. La Ertl, che si faceva chiamare ormai con il nome di battaglia di Imilla, lo uccise con una pistola registrata a nome di Giangiacomo Feltrinelli.

La Ertl venne a sua volta uccisa dalle forze di polizia boliviane il 12 maggio 1973.

Incredibili, sebbene tipici del clima culturale dell’epoca, sono i versi tratti da poesie della Ertl in cui i rivoluzionari sono paragonati a Gesù ed ai martiri cristiani (pp. 104 e 289 del volume di Schreiber):

Sì, tu m’insegnasti

che l’Uomo è Dio

…anche colui che è alla tua sinistra, sul Golgota

- il malvagio ladrone –

anche lui è un dio.

[…]

La Bolivia ha già un Cristo

Un Cristo con il suo fucile.

Crocefisso di proiettili.

In un triste settembre.

Quintanilla, Quintanilla…

Non troverai più pace.

Nelle tue notti…

Hai strappato la vita a Inti

E, speravi, al popolo intero

Ma Inti è morto

Per continuare a vivere nel cuore della gente.

7/ The Killing Machine. Che Guevara, from Communist Firebrand to Capitalist Brand, di Alvaro Vargas Llosa

Riprendiamo dal web un articolo di Alvaro Vargas Llosa pubblicato l’11/7/2005 su The Indipendent Review e su The New Republic (l’autore ha poi pubblicato in italiano Il mito Che Guevara e il futuro della libertà, Lindau, 2007). Restiamo a disposizione per l’immediata rimozione se la presenza sul nostro sito non fosse gradita a qualcuno degli aventi diritto. I neretti sono nostri ed hanno l’unico scopo di facilitare la lettura on-line.

Il Centro culturale Gli scritti (12/10/2014)

Che Guevara, who did so much (or was it so little?) to destroy capitalism, is now a quintessential capitalist brand. His likeness adorns mugs, hoodies, lighters, key chains, wallets, baseball caps, toques, bandannas, tank tops, club shirts, couture bags, denim jeans, herbal tea, and of course those omnipresent T-shirts with the photograph, taken by Alberto Korda, of the socialist heartthrob in his beret during the early years of the revolution, as Che happened to walk into the photographer’s viewfinder—and into the image that, thirty-eight years after his death, is still the logo of revolutionary (or is it capitalist?) chic. Sean O’Hagan claimed in The Observer that there is even a soap powder with the slogan “Che washes whiter.”

Che products are marketed by big corporations and small businesses, such as the Burlington Coat Factory, which put out a television commercial depicting a youth in fatigue pants wearing a Che T-shirt, or Flamingo’s Boutique in Union City, New Jersey, whose owner responded to the fury of local Cuban exiles with this devastating argument: “I sell whatever people want to buy.” Revolutionaries join the merchandising frenzy, too—from “The Che Store,” catering to “all your revolutionary needs” on the Internet, to the Italian writer Gianni Minà, who sold Robert Redford the movie rights to Che’s diary of his juvenile trip around South America in 1952 in exchange for access to the shooting of the film The Motorcycle Diaries so that Minà could produce his own documentary. Not to mention Alberto Granado, who accompanied Che on his youthful trip and advises documentarists, and now complains in Madrid, according to El País, over Rioja wine and duck magret, that the American embargo against Cuba makes it hard for him to collect royalties. To take the irony further: the building where Guevara was born in Rosario, Argentina, a splendid early twentieth-century edifice at the corner of Urquiza and Entre Ríos Streets, was until recently occupied by the private pension fund AFJP Máxima, a child of Argentina’s privatization of social security in the 1990s.

The metamorphosis of Che Guevara into a capitalist brand is not new, but the brand has been enjoying a revival of late—an especially remarkable revival, since it comes years after the political and ideological collapse of all that Guevara represented. This windfall is owed substantially to The Motorcycle Diaries, the film produced by Robert Redford and directed by Walter Salles. (It is one of three major motion pictures on Che either made or in the process of being made in the last two years; the other two have been directed by Josh Evans and Steven Soderbergh.) Beautifully shot against landscapes that have clearly eluded the eroding effects of polluting capitalism, the film shows the young man on a voyage of self-discovery as his budding social conscience encounters social and economic exploitation—laying the ground for a New Wave re-invention of the man whom Sartre once called the most complete human being of our era.

But to be more precise, the current Che revival started in 1997, on the thirtieth anniversary of his death, when five biographies hit the bookstores, and his remains were discovered near an airstrip at Bolivia’s Vallegrande airport, after a retired Bolivian general, in a spectacularly timed revelation, disclosed the exact location. The anniversary refocused attention on Freddy Alborta’s famous photograph of Che’s corpse laid out on a table, foreshortened and dead and romantic, looking like Christ in a Mantegna painting.

It is customary for followers of a cult not to know the real life story of their hero, the historical truth. (Many Rastafarians would renounce Haile Selassie if they had any notion of who he really was.) It is not surprising that Guevara’s contemporary followers, his new post-communist admirers, also delude themselves by clinging to a myth—except the young Argentines who have come up with an expression that rhymes perfectly in Spanish: “Tengo una remera del Che y no sé por qué,” or “I have a Che T-shirt and I don’t know why.”

Consider some of the people who have recently brandished or invoked Guevara’s likeness as a beacon of justice and rebellion against the abuse of power. In Lebanon, demonstrators protesting against Syria at the grave of former prime minister Rafiq Hariri carried Che’s image. Thierry Henry, a French soccer player who plays for Arsenal, in England, showed up at a major gala organized by FIFA, the world’s soccer body, wearing a red and black Che T-shirt. In a recent review in The New York Times of George A. Romero’s Land of the Dead, Manohla Dargis noted that “the greatest shock here may be the transformation of a black zombie into a righteous revolutionary leader,” and added, “I guess Che really does live, after all.” The soccer hero Maradona showed off the emblematic Che tattoo on his right arm during a trip where he met Hugo Chávez in Venezuela. In Stavropol, in southern Russia, protesters denouncing cash payments of welfare concessions took to the central square with Che flags. In San Francisco, City Lights Books, the legendary home of beat literature, treats visitors to a section devoted to Latin America in which half the shelves are taken up by Che books. José Luis Montoya, a Mexican police officer who battles drug crime in Mexicali, wears a Che sweatband because it makes him feel stronger. At the Dheisheh refugee camp on the West Bank, Che posters adorn a wall that pays tribute to the Intifada. A Sunday magazine devoted to social life in Sydney, Australia, lists the three dream guests at a dinner party: Alvar Aalto, Richard Branson, and Che Guevara. Leung Kwok-hung, the rebel elected to Hong Kong’s Legislative Council, defies Beijing by wearing a Che T-shirt. In Brazil, Frei Betto, President Lula da Silva’s adviser in charge of the high-profile “Zero Hunger” program, says that “we should have paid less attention to Trotsky and much more to Che Guevara.” And most famously, at this year’s Academy Awards ceremony Carlos Santana and Antonio Banderas performed the theme song from The Motorcycle Diaries, and Santana showed up wearing a Che T-shirt and a crucifix. The manifestations of the new cult of Che are everywhere. Once again the myth is firing up people whose causes for the most part represent the exact opposite of what Guevara was.

No man is without some redeeming qualities. In the case of Che Guevara, those qualities may help us to measure the gulf that separates reality from myth. His honesty (well, partial honesty) meant that he left written testimony of his cruelties, including the really ugly, though not the ugliest, stuff. His courage—what Castro described as “his way, in every difficult and dangerous moment, of doing the most difficult and dangerous thing”—meant that he did not live to take full responsibility for Cuba’s hell. Myth can tell you as much about an era as truth. And so it is that thanks to Che’s own testimonials to his thoughts and his deeds, and thanks also to his premature departure, we may know exactly how deluded so many of our contemporaries are about so much.

Guevara might have been enamored of his own death, but he was much more enamored of other people’s deaths. In April 1967, speaking from experience, he summed up his homicidal idea of justice in his “Message to the Tricontinental”: “hatred as an element of struggle; unbending hatred for the enemy, which pushes a human being beyond his natural limitations, making him into an effective, violent, selective, and cold-blooded killing machine.” His earlier writings are also peppered with this rhetorical and ideological violence. Although his former girlfriend Chichina Ferreyra doubts that the original version of the diaries of his motorcycle trip contains the observation that “I feel my nostrils dilate savoring the acrid smell of gunpowder and blood of the enemy,” Guevara did share with Granado at that very young age this exclamation: “Revolution without firing a shot? You’re crazy.” At other times the young bohemian seemed unable to distinguish between the levity of death as a spectacle and the tragedy of a revolution’s victims. In a letter to his mother in 1954, written in Guatemala, where he witnessed the overthrow of the revolutionary government of Jacobo Arbenz, he wrote: “It was all a lot of fun, what with the bombs, speeches, and other distractions to break the monotony I was living in.”

Guevara’s disposition when he traveled with Castro from Mexico to Cuba aboard the Granma is captured in a phrase in a letter to his wife that he penned on January 28, 1957, not long after disembarking, which was published in her book Ernesto: A Memoir of Che Guevara in Sierra Maestra: “Here in the Cuban jungle, alive and bloodthirsty.” This mentality had been reinforced by his conviction that Arbenz had lost power because he had failed to execute his potential enemies. An earlier letter to his former girlfriend Tita Infante had observed that “if there had been some executions, the government would have maintained the capacity to return the blows.” It is hardly a surprise that during the armed struggle against Batista, and then after the triumphant entry into Havana, Guevara murdered or oversaw the executions in summary trials of scores of people—proven enemies, suspected enemies, and those who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

In January 1957, as his diary from the Sierra Maestra indicates, Guevara shot Eutimio Guerra because he suspected him of passing on information: “I ended the problem with a .32 caliber pistol, in the right side of his brain.... His belongings were now mine.” Later he shot Aristidio, a peasant who expressed the desire to leave whenever the rebels moved on. While he wondered whether this particular victim “was really guilty enough to deserve death,” he had no qualms about ordering the death of Echevarría, a brother of one of his comrades, because of unspecified crimes: “He had to pay the price.” At other times he would simulate executions without carrying them out, as a method of psychological torture.

Luis Guardia and Pedro Corzo, two researchers in Florida who are working on a documentary about Guevara, have obtained the testimony of Jaime Costa Vázquez, a former commander in the revolutionary army known as “El Catalán,” who maintains that many of the executions attributed to Ramiro Valdés, a future interior minister of Cuba, were Guevara’s direct responsibility, because Valdés was under his orders in the mountains. “If in doubt, kill him” were Che’s instructions. On the eve of victory, according to Costa, Che ordered the execution of a couple dozen people in Santa Clara, in central Cuba, where his column had gone as part of a final assault on the island. Some of them were shot in a hotel, as Marcelo Fernándes-Zayas, another former revolutionary who later became a journalist, has written—adding that among those executed, known as casquitos, were peasants who had joined the army simply to escape unemployment.

But the “cold-blooded killing machine” did not show the full extent of his rigor until, immediately after the collapse of the Batista regime, Castro put him in charge of La Cabaña prison. (Castro had a clinically good eye for picking the right person to guard the revolution against infection.) San Carlos de La Cabaña was a stone fortress used to defend Havana against English pirates in the eighteenth century; later it became a military barracks. In a manner chillingly reminiscent of Lavrenti Beria, Guevara presided during the first half of 1959 over one of the darkest periods of the revolution. José Vilasuso, a lawyer and a professor at Universidad Interamericana de Bayamón in Puerto Rico, who belonged to the body in charge of the summary judicial process at La Cabaña, told me recently that Che was in charge of the Comisión Depuradora. The process followed the law of the Sierra: there was a military court and Che’s guidelines to us were that we should act with conviction, meaning that they were all murderers and the revolutionary way to proceed was to be implacable. My direct superior was Miguel Duque Estrada. My duty was to legalize the files before they were sent on to the Ministry. Executions took place from Monday to Friday, in the middle of the night, just after the sentence was given and automatically confirmed by the appellate body. On the most gruesome night I remember, seven men were executed.

Javier Arzuaga, the Basque chaplain who gave comfort to those sentenced to die and personally witnessed dozens of executions, spoke to me recently from his home in Puerto Rico. A former Catholic priest, now seventy-five, who describes himself as “closer to Leonardo Boff and Liberation Theology than to the former Cardinal Ratzinger,” he recalls that there were about eight hundred prisoners in a space fit for no more than three hundred: former Batista military and police personnel, some journalists, a few businessmen and merchants. The revolutionary tribunal was made of militiamen. Che Guevara presided over the appellate court. He never overturned a sentence. I would visit those on death row at the galera de la muerte. A rumor went around that I hypnotized prisoners because many remained calm, so Che ordered that I be present at the executions. After I left in May, they executed many more, but I personally witnessed fifty-five executions. There was an American, Herman Marks, apparently a former convict. We called him “the butcher” because he enjoyed giving the order to shoot. I pleaded many times with Che on behalf of prisoners. I remember especially the case of Ariel Lima, a young boy. Che did not budge. Nor did Fidel, whom I visited. I became so traumatized that at the end of May 1959 I was ordered to leave the parish of Casa Blanca, where La Cabaña was located and where I had held Mass for three years. I went to Mexico for treatment. The day I left, Che told me we had both tried to bring one another to each other’s side and had failed. His last words were: “When we take our masks off, we will be enemies.”

How many people were killed at La Cabaña? Pedro Corzo offers a figure of some two hundred, similar to that given by Armando Lago, a retired economics professor who has compiled a list of 179 names as part of an eight-year study on executions in Cuba. Vilasuso told me that four hundred people were executed between January and the end of June in 1959 (at which point Che ceased to be in charge of La Cabaña). Secret cables sent by the American Embassy in Havana to the State Department in Washington spoke of “over 500.” According to Jorge Castañeda, one of Guevara’s biographers, a Basque Catholic sympathetic to the revolution, the late Father Iñaki de Aspiazú, spoke of seven hundred victims. Félix Rodríguez, a CIA agent who was part of the team in charge of the hunt for Guevara in Bolivia, told me that he confronted Che after his capture about “the two thousand or so” executions for which he was responsible during his lifetime. “He said they were all CIA agents and did not address the figure,” Rodríguez recalls. The higher figures may include executions that took place in the months after Che ceased to be in charge of the prison.

Which brings us back to Carlos Santana and his chic Che gear. In an open letter published in El Nuevo Herald on March 31 of this year, the great jazz musician Paquito D’Rivera castigated Santana for his costume at the Oscars, and added: “One of those Cubans [at La Cabaña] was my cousin Bebo, who was imprisoned there precisely for being a Christian. He recounts to me with infinite bitterness how he could hear from his cell in the early hours of dawn the executions, without trial or process of law, of the many who died shouting, ‘Long live Christ the King!’”

Che’s lust for power had other ways of expressing itself besides murder. The contradiction between his passion for travel—a protest of sorts against the constraints of the nation-State—and his impulse to become himself an enslaving state over others is poignant. In writing about Pedro Valdivia, the conquistador of Chile, Guevara reflected: “He belonged to that special class of men the species produces every so often, in whom a craving for limitless power is so extreme that any suffering to achieve it seems natural.” He might have been describing himself. At every stage of his adult life, his megalomania manifested itself in the predatory urge to take over other people’s lives and property, and to abolish their free will.

In 1958, after taking the city of Sancti Spiritus, Guevara unsuccessfully tried to impose a kind of sharia, regulating relations between men and women, the use of alcohol, and informal gambling—a puritanism that did not exactly characterize his own way of life. He also ordered his men to rob banks, a decision that he justified in a letter to Enrique Oltuski, a subordinate, in November of that year: “The struggling masses agree to robbing banks because none of them has a penny in them.” This idea of revolution as a license to re-allocate property as he saw fit led the Marxist Puritan to take over the mansion of an emigrant after the triumph of the revolution.

The urge to dispossess others of their property and to claim ownership of others’ territory was central to Guevara’s politics of raw power. In his memoirs, the Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser records that Guevara asked him how many people had left his country because of land reform. When Nasser replied that no one had left, Che countered in anger that the way to measure the depth of change is by the number of people “who feel there is no place for them in the new society.” This predatory instinct reached a pinnacle in 1965, when he started talking, God-like, about the “New Man” that he and his revolution would create.

Che’s obsession with collectivist control led him to collaborate on the formation of the security apparatus that was set up to subjugate six and a half million Cubans. In early 1959, a series of secret meetings took place in Tarará, near Havana, at the mansion to which Che temporarily withdrew to recover from an illness. That is where the top leaders, including Castro, designed the Cuban police state. Ramiro Valdés, Che’s subordinate during the guerrilla war, was put in charge of G-2, a body modeled on the Cheka. Angel Ciutah, a veteran of the Spanish Civil War sent by the Soviets who had been very close to Ramón Mercader, Trotsky’s assassin, and later befriended Che, played a key role in organizing the system, together with Luis Alberto Lavandeira, who had served the boss at La Cabaña. Guevara himself took charge of G-6, the body tasked with the ideological indoctrination of the armed forces. The U.S.-backed Bay of Pigs invasion in April 1961 became the perfect occasion to consolidate the new police state, with the rounding up of tens of thousands of Cubans and a new series of executions. As Guevara himself told the Soviet ambassador Sergei Kudriavtsev, counterrevolutionaries were never “to raise their head again.”

“Counterrevolutionary” is the term that was applied to anyone who departed from dogma. It was the communist synonym for “heretic.” Concentration camps were one form in which dogmatic power was employed to suppress dissent. History attributes to the Spanish general Valeriano Weyler, the captain-general of Cuba at the end of the nineteenth century, the first use of the word “concentration” to describe the policy of surrounding masses of potential opponents—in his case, supporters of the Cuban independence movement—with barbed wire and fences. How fitting that Cuba’s revolutionaries more than half a century later were to take up this indigenous tradition. In the beginning, the revolution mobilized volunteers to build schools and to work in ports, plantations, and factories—all exquisite photo-ops for Che the stevedore, Che the cane-cutter, Che the clothmaker. It was not long before volunteer work became a little less voluntary:

the first forced labor camp, Guanahacabibes, was set up in western Cuba at the end of 1960. This is how Che explained the function performed by this method of confinement: “[We] only send to Guanahacabibes those doubtful cases where we are not sure people should go to jail ... people who have committed crimes against revolutionary morals, to a lesser or greater degree.... It is hard labor, not brute labor, rather the working conditions there are hard.”

This camp was the precursor to the eventual systematic confinement, starting in 1965 in the province of Camaguey, of dissidents, homosexuals, AIDS victims, Catholics, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Afro-Cuban priests, and other such scum, under the banner of Unidades Militares de Ayuda a la Producción, or Military Units to Help Production. Herded into buses and trucks, the “unfit” would be transported at gunpoint into concentration camps organized on the Guanahacabibes mold. Some would never return; others would be raped, beaten, or mutilated; and most would be traumatized for life, as Néstor Almendros’s wrenching documentary Improper Conduct showed the world a couple of decades ago.

So Time magazine may have been less than accurate in August 1960 when it described the revolution’s division of labor with a cover story featuring Che Guevara as the “brain” and Fidel Castro as the “heart” and Raúl Castro as the “fist.” But the perception reflected Guevara’s crucial role in turning Cuba into a bastion of totalitarianism. Che was a somewhat unlikely candidate for ideological purity, given his bohemian spirit, but during the years of training in Mexico and in the ensuing period of armed struggle in Cuba he emerged as the communist ideologue infatuated with the Soviet Union, much to the discomfort of Castro and others who were essentially opportunists using whatever means were necessary to gain power. When the would-be revolutionaries were arrested in Mexico in 1956, Guevara was the only one who admitted that he was a communist and was studying Russian. (He spoke openly about his relationship with Nikolai Leonov from the Soviet Embassy.) During the armed struggle in Cuba, he forged a strong alliance with the Popular Socialist Party (the island’s Communist Party) and with Carlos Rafael Rodríguez, a key player in the conversion of Castro’s regime to communism.

This fanatical disposition made Che into a linchpin of the “Sovietization” of the revolution that had repeatedly boasted about its independent character. Very soon after the barbudos came to power, Guevara took part in negotiations with Anastas Mikoyan, the Soviet deputy prime minister, who visited Cuba. He was entrusted with the mission of furthering Soviet-Cuban negotiations during a visit to Moscow in late 1960. (It was part of a long trip in which Kim Il Sung’s North Korea was the country that impressed him “the most.”) Guevara’s second trip to Russia, in August 1962, was even more significant, because it sealed the deal to turn Cuba into a Soviet nuclear beachhead. He met Khrushchev in Yalta to finalize details on an operation that had already begun and involved the introduction of forty-two Soviet missiles, half of which were armed with nuclear warheads, as well as launchers and some forty-two thousand soldiers. After pressing his Soviet allies on the danger that the United States might find out what was happening, Guevara obtained assurances that the Soviet navy would intervene—in other words, that Moscow was ready to go to war.

According to Philippe Gavi’s biography of Guevara, the revolutionary had bragged that “this country is willing to risk everything in an atomic war of unimaginable destructiveness to defend a principle.” Just after the Cuban missile crisis ended—with Khrushchev reneging on the promise made in Yalta and negotiating a deal with the United States behind Castro’s back that included the removal of American missiles from Turkey—Guevara told a British communist daily: “If the rockets had remained, we would have used them all and directed them against the very heart of the United States, including New York, in our defense against aggression.” And a couple of years later, at the United Nations, he was true to form: “As Marxists we have maintained that peaceful coexistence among nations does not include coexistence between exploiters and the exploited.”

Guevara distanced himself from the Soviet Union in the last years of his life. He did so for the wrong reasons, blaming Moscow for being too soft ideologically and diplomatically, for making too many concessions—unlike Maoist China, which he came to see as a haven of orthodoxy. In October 1964, a memo written by Oleg Daroussenkov, a Soviet official close to him, quotes Guevara as saying: “We asked the Czechoslovaks for arms; they turned us down. Then we asked the Chinese; they said yes in a few days, and did not even charge us, stating that one does not sell arms to a friend.” In fact, Guevara resented the fact that Moscow was asking other members of the communist bloc, including Cuba, for something in return for its colossal aid and political support. His final attack on Moscow came in Algiers, in February 1965, at an international conference, where he accused the Soviets of adopting the “law of value,” that is, capitalism. His break with the Soviets, in sum, was not a cry for independence. It was an Enver Hoxha–like howl for the total subordination of reality to blind ideological orthodoxy.

The great revolutionary had a chance to put into practice his economic vision—his idea of social justice—as head of the National Bank of Cuba and of the Department of Industry of the National Institute of Agrarian Reform at the end of 1959, and, starting in early 1961, as minister of industry. The period in which Guevara was in charge of most of the Cuban economy saw the near-collapse of sugar production, the failure of industrialization, and the introduction of rationing—all this in what had been one of Latin America’s four most economically successful countries since before the Batista dictatorship.

His stint as head of the National Bank, during which he printed bills signed “Che,” has been summarized by his deputy, Ernesto Betancourt: “[He] was ignorant of the most elementary economic principles.” Guevara’s powers of perception regarding the world economy were famously expressed in 1961, at a hemispheric conference in Uruguay, where he predicted a 10 percent rate of growth for Cuba “without the slightest fear,” and, by 1980, a per capita income greater than that of “the U.S. today.” In fact, by 1997, the thirtieth anniversary of his death, Cubans were dieting on a ration of five pounds of rice and one pound of beans per month; four ounces of meat twice a year; four ounces of soybean paste per week; and four eggs per month.

Land reform took land away from the rich, but gave it to the bureaucrats, not to the peasants. (The decree was written in Che’s house.) In the name of diversification, the cultivated area was reduced and manpower distracted toward other activities. The result was that between 1961 and 1963, the harvest was down by half, to a mere 3.8 million metric tons. Was this sacrifice justified by progress in Cuban industrialization? Unfortunately, Cuba had no raw materials for heavy industry, and, as a consequence of the revolutionary redistribution, it had no hard currency with which to buy them—or even basic goods. By 1961, Guevara was having to give embarrassing explanations to the workers at the office: “Our technical comrades at the companies have made a toothpaste ... which is as good as the previous one; it cleans just the same, though after a while it turns to stone.” By 1963, all hopes of industrializing Cuba were abandoned, and the revolution accepted its role as a colonial provider of sugar to the Soviet bloc in exchange for oil to cover its needs and to re-sell to other countries. For the next three decades, Cuba would survive on a Soviet subsidy of somewhere between $65 billion and $100 billion.

Having failed as a hero of social justice, does Guevara deserve a place in the history books as a genius of guerrilla warfare? His greatest military achievement in the fight against Batista—taking the city of Santa Clara after ambushing a train with heavy reinforcements—is seriously disputed. Numerous testimonies indicate that the commander of the train surrendered in advance, perhaps after taking bribes. (Gutiérrez Menoyo, who led a different guerrilla group in that area, is among those who have decried Cuba’s official account of Guevara’s victory.) Immediately after the triumph of the revolution, Guevara organized guerrilla armies in Nicaragua, the Dominican Republic, Panama, and Haiti—all of which were crushed. In 1964, he sent the Argentine revolutionary Jorge Ricardo Masetti to his death by persuading him to mount an attack on his native country from Bolivia, just after representative democracy had been restored to Argentina.

Particularly disastrous was the Congo expedition in 1965. Guevara sided with two rebels—Pierre Mulele in the west and Laurent Kabila in the east—against the ugly Congolese government, which was sustained by the United States as well as by South African and exiled Cuban mercenaries. Mulele had taken over Stanleyville earlier before being driven back. During his reign of terror, as V.S. Naipaul has written, he murdered all the people who could read and all those who wore a tie. As for Guevara’s other ally, Laurent Kabila, he was merely lazy and corrupt at the time; but the world would find out in the 1990s that he, too, was a killing machine. In any event, Guevara spent most of 1965 helping the rebels in the east before fleeing the country ignominiously. Soon afterward, Mobutu came to power and installed a decades-long tyranny. (In Latin American countries too, from Argentina to Peru, Che-inspired revolutions had the practical result of reinforcing brutal militarism for many years.)

In Bolivia, Che was defeated again, and for the last time. He misread the local situation. There had been an agrarian reform years before; the government had respected many of the peasant communities’ institutions; and the army was close to the United States despite its nationalism. “The peasant masses don’t help us at all” was Guevara’s melancholy conclusion in his Bolivian diary. Even worse, Mario Monje, the local communist leader, who had no stomach for guerrilla warfare after having been humiliated at the elections, led Guevara to a vulnerable location in the southeast of the country. The circumstances of Che’s capture at Yuro ravine, soon after meeting the French intellectual Régis Debray and the Argentine painter Ciro Bustos, both of whom were arrested as they left the camp, was, like most of the Bolivian expedition, an amateur’s affair.

Guevara was certainly bold and courageous, and quick at organizing life on a military basis in the territories under his control, but he was no General Giap. His book Guerrilla Warfare teaches that popular forces can beat an army, that it is not necessary to wait for the right conditions because an insurrectional foco (or small group of revolutionaries) can bring them about, and that the fight must primarily take place in the countryside. (In his prescription for guerrilla warfare, he also reserves for women the roles of cooks and nurses.) However, Batista’s army was not an army, but a corrupt bunch of thugs with no motivation and not much organization; and guerrilla focos, with the exception of Nicaragua, all ended up in ashes for the foquistas; and Latin America has turned 70 percent urban in these last four decades. In this regard, too, Che Guevara was a callous fool.

In the last few decades of the nineteenth century, Argentina had the second-highest growth rate in the world. By the 1890s, the real income of Argentine workers was greater than that of Swiss, German, and French workers. By 1928, that country had the twelfth-highest per capita GDP in the world. That achievement, which later generations would ruin, was in large measure due to Juan Bautista Alberdi.

Like Guevara, Alberdi liked to travel: he walked through the pampas and deserts from north to south at the age of fourteen, all the way to Buenos Aires. Like Guevara, Alberdi opposed a tyrant, Juan Manuel Rosas. Like Guevara, Alberdi got a chance to influence a revolutionary leader in power—Justo José de Urquiza, who toppled Rosas in 1852. And like Guevara, Alberdi represented the new government on world tours, and died abroad. But unlike the old and new darling of the left, Alberdi never killed a fly. His book, Bases y puntos de partida para la organización de la República Argentina, was the foundation of the Constitution of 1853 that limited government, opened trade, encouraged immigration, and secured property rights, thereby inaugurating a seventy-year period of astonishing prosperity. He did not meddle in the affairs of other nations, opposing his country’s war against Paraguay. His likeness does not adorn Mike Tyson’s abdomen.

Note al testo

[1] Dal capitolo "L'America Latina alla prova" a pag. 608 dell'opera: Il Libro Nero del Comunismo, 1998, Arnoldo Mondadori Editore S.p.A., Milano.

[2] Dall'articolo dello scrittore Alvaro Vargas Llosa riportato in http://www.independent.org/newsroom/article.asp?id=1535 in cui si afferma che "In January 1957, as his diary from the Sierra Maestra indicates, Guevara shot Eutimio Guerra because he suspected him of passing on information: “I ended the problem with a .32 caliber pistol, in the right side of his brain.... His belongings were now mine.” Later he shot Aristidio, a peasant who expressed the desire to leave whenever the rebels moved on. While he wondered whether this particular victim “was really guilty enough to deserve death,” he had no qualms about ordering the death of Echevarría, a brother of one of his comrades, because of unspecified crimes: “He had to pay the price.”"

Dall'articolo dello scrittore Alvaro Vargas Llosa riportato in http://www.independent.org/newsroom/article.asp?id=1535 in cui si afferma che "At other times he would simulate executions without carrying them out, as a method of psychological torture."

Dall'articolo dello scrittore Alvaro Vargas Llosa riportato in http://www.independent.org/newsroom/article.asp?id=1535 in cui si afferma che "In 1958, after taking the city of Sancti Spiritus, Guevara unsuccessfully tried to impose a kind of sharia, regulating relations between men and women, the use of alcohol, and informal gambling—a puritanism that did not exactly characterize his own way of life. He also ordered his men to rob banks, a decision that he justified in a letter to Enrique Oltuski, a subordinate, in November of that year: “The struggling masses agree to robbing banks because none of them has a penny in them.” This idea of revolution as a license to re-allocate property as he saw fit led the Marxist Puritan to take over the mansion of an emigrant after the triumph of the revolution."

[3] Ad esempio Andrea Morigi in "Che Guevara, il bandito santificato", 2007, Il Timone.

[4] Considerato, data la morte avvenuta in quello stesso anno, il testamento politico di Guevara: http://www.ecn.org/asicuba/cuba/tricont2.htm

[5] In quattro lingue, ovverosia spagnolo, inglese, francese e italiano, a cura della Segreteria Esecutiva dell'OSPAAAL, l'Organizzazione della Solidarietà dei Popoli d'Africa, Asia e America Latina e distribuito in Europa dalle Edizioni Maspero a Parigi e dalla Libreria Feltrinelli a Milano

[6] Citato in Guido Crainz, Storia del miracolo italiano, Donzelli, 2003.

[7] Che Guevara: La rivoluzione dei popoli oppressi.

[8] Gómez Treto 1991, p. 115. "The Penal Law of the War of Independence (July 28, 1896) was reinforced by Rule 1 of the Penal Regulations of the Rebel Army, approved in the Sierra Maestra February 21, 1958, and published in the army's official bulletin (Ley penal de Cuba en armas, 1959)" (Gómez Treto 1991, p. 123).

[9] Antonio Moscato, Breve storia di Cuba, terza edizione riveduta e ampliata, Datanews, Roma, 2006, p. 78.

[10] Niess 2007, p. 60.

[11] Different sources cite different numbers of executions. Anderson (1997) gives the number specifically at La Cabaña prison as 55 (p. 387.), while also stating that as a whole "several hundred people were officially tried and executed across Cuba" (p. 387). This is supported by Lago who gives the figure as 216 documented executions across Cuba in two years.

Secondo Robertio Occhi i fucilati in tutta Cuba per crimini di guerra furono, nel biennio 1959-1960, tra le 200 e le 500 persone. Vedi Roberto Occhi, Che Guevara. La più completa biografia, Verdechiaro, 2007, pag. 147

Paco Ignacio Taibo II riporta la testimonianza di Duque de Estrada, secondo il quale i fucilati furono 55. Vedi Taibo II, p. 359.

[12] Roberto Occhi, Che Guevara. La più completa biografia, Verdechiaro, 2007, p. 147.

[14] Dal capitolo "L'America Latina alla prova" dell'opera Il Libro Nero del Comunismo, 1998, Arnoldo Mondadori Editore S.p.A., Milano

[15] Dal capitolo "L'America Latina alla prova" dell'opera Il Libro Nero del Comunismo, 1998, Arnoldo Mondadori Editore S.p.A., Milano.

[16] Antonio Moscato, Breve storia di Cuba, terza edizione riveduta e ampliata, Datanews, Roma, 2006, pag. 78.

[17] Dall'articolo riportato in http://www.independent.org/newsroom/article.asp?id=1535 in cui afferma che "How many people were killed at La Cabaña? Pedro Corzo offers a figure of some two hundred, similar to that given by Armando Lago, a retired economics professor who has compiled a list of 179 names as part of an eight-year study on executions in Cuba. Vilasuso told me that four hundred people were executed between January and the end of June in 1959 (at which point Che ceased to be in charge of La Cabaña). Secret cables sent by the American Embassy in Havana to the State Department in Washington spoke of “over 500.” According to Jorge Castañeda, one of Guevara’s biographers, a Basque Catholic sympathetic to the revolution, the late Father Iñaki de Aspiazú, spoke of seven hundred victims. Félix Rodríguez, a CIA agent who was part of the team in charge of the hunt for Guevara in Bolivia, told me that he confronted Che after his capture about “the two thousand or so” executions for which he was responsible during his lifetime. “He said they were all CIA agents and did not address the figure,” Rodríguez recalls. The higher figures may include executions that took place in the months after Che ceased to be in charge of the prison."

[18] Lo afferma in "Il Mito di Che Guevara e il Futuro della Libertà", pubblicato nel 2005.

[19] Paco Ignacio Taibo II, Vita e morte di Ernesto Che Guevara, edizione ampliata, Il Saggiatore, 2004 pp. 455-457.

[20] Dalla dittatura di Castro e Che Guevara solo morte e povertà.

Dal capitolo "L'America Latina alla prova" dell'opera: Il Libro Nero del Comunismo, 1998, Arnoldo Mondadori Editore S.p.A., Milano.

Armando Valladares, Contro ogni speranza. Dal fondo delle carceri di Castro, SugarCo, Milano 1987.

Dall'articolo dello scrittore Alvaro Vargas Llosa riportato in http://www.independent.org/newsroom/article.asp?id=1535 in cui si afferma che "Counterrevolutionary” is the term that was applied to anyone who departed from dogma. It was the communist synonym for “heretic.” Concentration camps were one form in which dogmatic power was employed to suppress dissent. History attributes to the Spanish general Valeriano Weyler, the captain-general of Cuba at the end of the nineteenth century, the first use of the word “concentration” to describe the policy of surrounding masses of potential opponents—in his case, supporters of the Cuban independence movement—with barbed wire and fences. How fitting that Cuba’s revolutionaries more than half a century later were to take up this indigenous tradition. In the beginning, the revolution mobilized volunteers to build schools and to work in ports, plantations, and factories—all exquisite photo-ops for Che the stevedore, Che the cane-cutter, Che the clothmaker. It was not long before volunteer work became a little less voluntary: the first forced labor camp, Guanahacabibes, was set up in western Cuba at the end of 1960. This is how Che explained the function performed by this method of confinement: “[We] only send to Guanahacabibes those doubtful cases where we are not sure people should go to jail ... people who have committed crimes against revolutionary morals, to a lesser or greater degree.... It is hard labor, not brute labor, rather the working conditions there are hard."

[21] Dall'articolo dello scrittore Alvaro Vargas Llosa riportato in http://www.independent.org/newsroom/article.asp?id=1535.

Félix Luis Viera, Il lavoro vi farà uomini. Omosessuali e dissidenti nei gulag di Fidel Castro, Edizioni Cargo, 2005

[22] Vincenzo Merlo, Che Guevara non studiò a Parigi in www.ragionpolitica.it.

[23] Il Corriere Del Sud - Articoli - Il mito di Che Guevara

[24] Dall'articolo dello scrittore Alvaro Vargas Llosa riportato in http://www.independent.org/newsroom/article.asp?id=1535 in cui si afferma, citando il periodico americano Time Magazine, che "so Time magazine may have been less than accurate in August 1960 when it described the revolution’s division of labor with a cover story featuring Che Guevara as the “brain” and Fidel Castro as the “heart” and Raúl Castro as the “fist.” But the perception reflected Guevara’s crucial role in turning Cuba into a bastion of totalitarianism. "

[25] Dall'articolo dello scrittore Alvaro Vargas Llosa riportato in http://www.independent.org/newsroom/article.asp?id=1535 in cui afferma che "Land reform took land away from the rich, but gave it to the bureaucrats, not to the peasants. (The decree was written in Che’s house.) In the name of diversification, the cultivated area was reduced and manpower distracted toward other activities. The result was that between 1961 and 1963, the harvest was down by half, to a mere 3.8 million metric tons. Was this sacrifice justified by progress in Cuban industrialization? Unfortunately, Cuba had no raw materials for heavy industry, and, as a consequence of the revolutionary redistribution, it had no hard currency with which to buy them—or even basic goods. By 1961, Guevara was having to give embarrassing explanations to the workers at the office: “Our technical comrades at the companies have made a toothpaste ... which is as good as the previous one; it cleans just the same, though after a while it turns to stone.” By 1963, all hopes of industrializing Cuba were abandoned, and the revolution accepted its role as a colonial provider of sugar to the Soviet bloc in exchange for oil to cover its needs and to re-sell to other countries. For the next three decades, Cuba would survive on a Soviet subsidy of somewhere between $65 billion and $100 billion." e che "In his memoirs, the Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser records that Guevara asked him how many people had left his country because of land reform. When Nasser replied that no one had left, Che countered in anger that the way to measure the depth of change is by the number of people “who feel there is no place for them in the new society.”"

[26] Fidel Castro chiede scusa ai gay «Perseguitati, la colpa è mia».