La figlia di Shakespeare, Susanna, indagata per non aver partecipato alla celebrazione della Pasqua con ministro anglicano. Susanna, William Shakespeare’s daughter, is cited in the local church court for her failure to receive communion. May 5, 1606, di Robert Bearman

Riprendiamo sul nostro sito un articolo di Robert Bearman (https://shakespearedocumented.folger.edu/resource/document/susanna-william-shakespeare-s-daughter-cited-local-church-court-her-failure#:~:text=However%2C%20the%20eight%20sittings%20between,last%E2%80%9D%20(April%2020), Kent History and Library Centre, Maidstone- Kent County Council, dal sito https://shakespearedocumented.folger.edu/ , pubblicata il 27/1/2020. Restiamo a disposizione per l’immediata rimozione se la sua presenza non fosse gradita a qualcuno degli aventi diritto. Per approfondimenti, cfr. la sezione Maestri nello Spirito e I luoghi di Tommaso Moro a Londra, di Andrea Lonardo.

Il Centro culturale Gli scritti (14/10/2021)

N.B. de Gli scritti

Lo studio che segue non dimostra che Shakespeare e la sua famiglia fossero cattolici – la cosa resta discussa – ma permette di rendersi conto di quanto fossero accurate la censura e l’inquisizione nell’Inghilterra elisabettiana, mirante a recidere ogni rapporto di qualsivoglia persona con la fede cattolica. Siamo nel 1605, negli anni a Roma di Caravaggio e Galilei, e la situazione nell’Inghilterra protestante era certamente peggiore.

Under the Elizabethan Settlement, as defined in the Act of Supremacy of 1558 and the Act of Uniformity of 1559, every man and woman was expected to receive Holy Communion three times a year. Easter had to be one of these three occasions. Those who failed to comply were suspected of sympathy with the old religion and risked prosecution in the secular courts as recusants.

In addition to the secular courts, the church also had its own courts to enforce discipline in spiritual matters, including church attendance. These were organized on a diocesan basis, but some parishes, including Stratford-upon-Avon, enjoyed what was known as a “peculiar jurisdiction.” In Stratford’s case, the incumbent vicar enjoyed independence from the bishop’s oversight every two years out of three, including the keeping of his own courts.

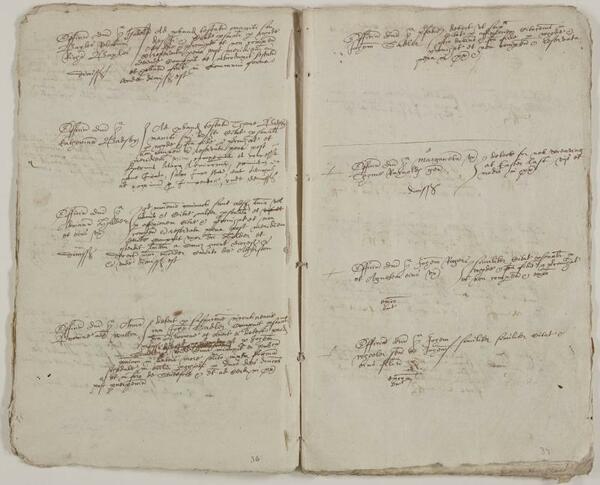

The registers of this court survive for the years 1590-1608 and 1622-24 (with a single case recorded in 1616) though there are gaps in the 1590s and early 1600’s, implying that the court’s proceedings were not always fully recorded. However, the eight sittings between May 1606 and December 1608 are particularly well documented.

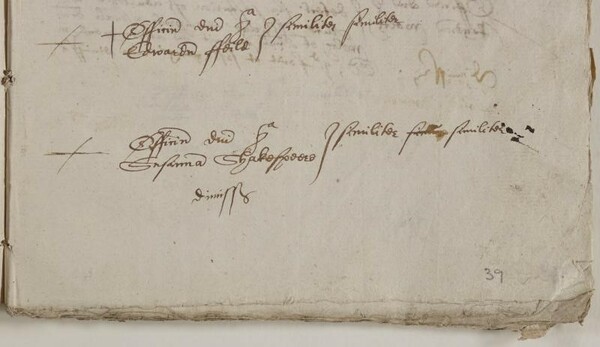

In the first of these registers, as shown here, Susanna Shakespeare was cited on May 5, 1606 with twenty other parishioners for their failure to receive communion at “Easter last” (April 20). The heavily abbreviated entry “contra Susannam Shakespeere” is followed by the words “similiter, similiter,” indicating that her case arose, and was treated, in the same way as the four preceding ones: namely, that John Ward, the court’s official, had reported Susanna for non-reception but that on her failure to appear on May 5, the penalty was reserved to the next court. Below the entry is the word “dismissa,” indicating that the charge was not pursued.

This citation needs to be seen in context. After the Gunpowder Plot was uncovered in November 1605, Parliament quickly put an Act in place imposing heavy fines on those who refused to receive Holy Communion at least once a year. It is therefore scarcely surprising that, the following Easter, church authorities would be keen to appear vigilant in observing the spirit of this new law. This was especially felt in Stratford, since Ambrose Rookwood (one of the Gunpowder Plot conspirators) had recently leased nearby Clopton House, bringing the area to the government’s attention. The infrequency with which other cases of non-reception came to the Stratford court’s attention over the period covered by this first register more or less establishes that the May 1606 citations were the result of a specific reaction to these post-Gunpowder Plot circumstances. Indeed, cases of “non-reception” only appeared three times between 1590 and 1608. Furthermore we need to take into account four other lists of recusants which survive for these years: one list, with thirty Stratford names, dates to August 1605, two to 1606, and another to ca. 1607. Susanna’s does not appear in any of these, nor do the seventeen others presented alongside her in the Stratford court in May 1606. Conversely, eight well-known Catholics who occur consistently in all four lists are absent from this Peculiar Court list, as are three others who feature in three of the four lists.

Susanna’s case may have been ultimately dismissed because she attended the next court, as prescribed, and apologized for her lapse. However, there is no record of another sitting of the court until December 2. At this court, three people cited in May appeared and promised to receive Communion in the future, whereupon the cases against them were dismissed. At the same time, three out of four who had been excommunicated as a result of their non-reception were also pardoned.

Notes added against eight other names in the initial list indicate that they had promised (or had been ordered) to receive in future, that they had done so, and that the case had been dismissed. Susanna Shakespeare’s case, however, following her non-appearance, had simply been referred to the next court and then dismissed. Only two other cases, against Thomas Stanney and his wife, have exactly the same annotation as Susanna’s, namely to the effect that no further action needed to be taken, essentially confirming that they were of no consequence. The following month (on June 5) Susanna married John Hall, noted later in his career for his Protestant, if not Puritan, views.